1. I think that you and I are about the only members who are interested in Reed-Kellogg.

It was from you, in a different online aspect (on a different forum), that I learned of the existence of the Reed-Kellogg system long ago. Subsequently, I found out that my parents had been taught, in the 1950s and 1960s, how to diagram sentences using that method, which, sadly, did not form part of my "grammar school" education in California, in the late 1980s, when hardly any grammar at all was taught to us native-speaking youngsters.

Recently I have tried to pick up the system, but I have tried to swallow it whole rather than learn it piecemeal in a disciplined fashion. (The level of detail it depicts is somewhat restricted relative to Chomskyan generative syntax, which I have taken several courses in at the university.) Already I have used the Reed-Kellogg system in an advanced-low ESL composition class that I teach, but only to illustrate things like subject-verb agreement and relative-clause modification.

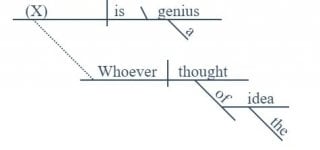

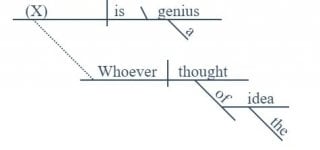

3. I thank you for your beautiful diagram. It perfectly shows how that sentence should be diagrammed if one believes the words "Whoever thought of the idea" is a noun clause that serves as the subject of the sentence.

4. If I am not mistaken (and I could easily be), House and Harman would diagram it differently (based on their diagram on page 358). [. . .]

Since you know Reed-Kellogg, maybe all that I have to say is the following: Diagram "whoever [which means "who" in their diagram] thought of the idea" as an adjective clause that modifies the sentence "X is a genius." ("X" is the implied antecedent "anyone.") In other words, diagram it as "Anyone who thought of the idea is a genius."

This is fascinating. Thank you for giving that reference again, which I have now checked. I am amazed to discover that Pence and Emery, using the same diagramming system that House and Harman used (namely, the Reed-Kellogg system), diagram what I call free relative clauses in an entirely different way. It is not just for the sentence

I shall take whatever wage is offered me that Pence and Emery use the clause-topped pedestal structure. They likewise diagram the word-string

whoever asks for it in indirect-object position in the sentence

We will make whoever asks for it a quotation for the whole job using that structure (see p. 399, 2nd Ed.).

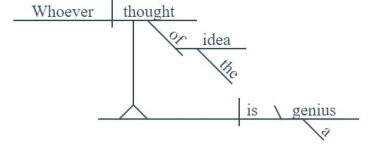

I have attached a new diagram, using House and Harman's approach (again, within the Reed-Kellogg diagramming system). I find it interesting that they say that the indefinite relative pronouns in such structures have "unexpressed antecedents" (p. 357), which they also describe as "understood" (

ibid.). It is as though they are building in a level of logical structure within the Reed-Kellogg diagrams -- in which there is a relative-clause modifier of "X" -- whereas Pence and Emery represent such free relatives (or syntactic entities) simply as clausal subjects or objects.